silver gelatin photography, (40x50cm)

A selection of photographs from 1991 - 1994 (click on next sitepage for the Self Portraits 2003 - 2023)

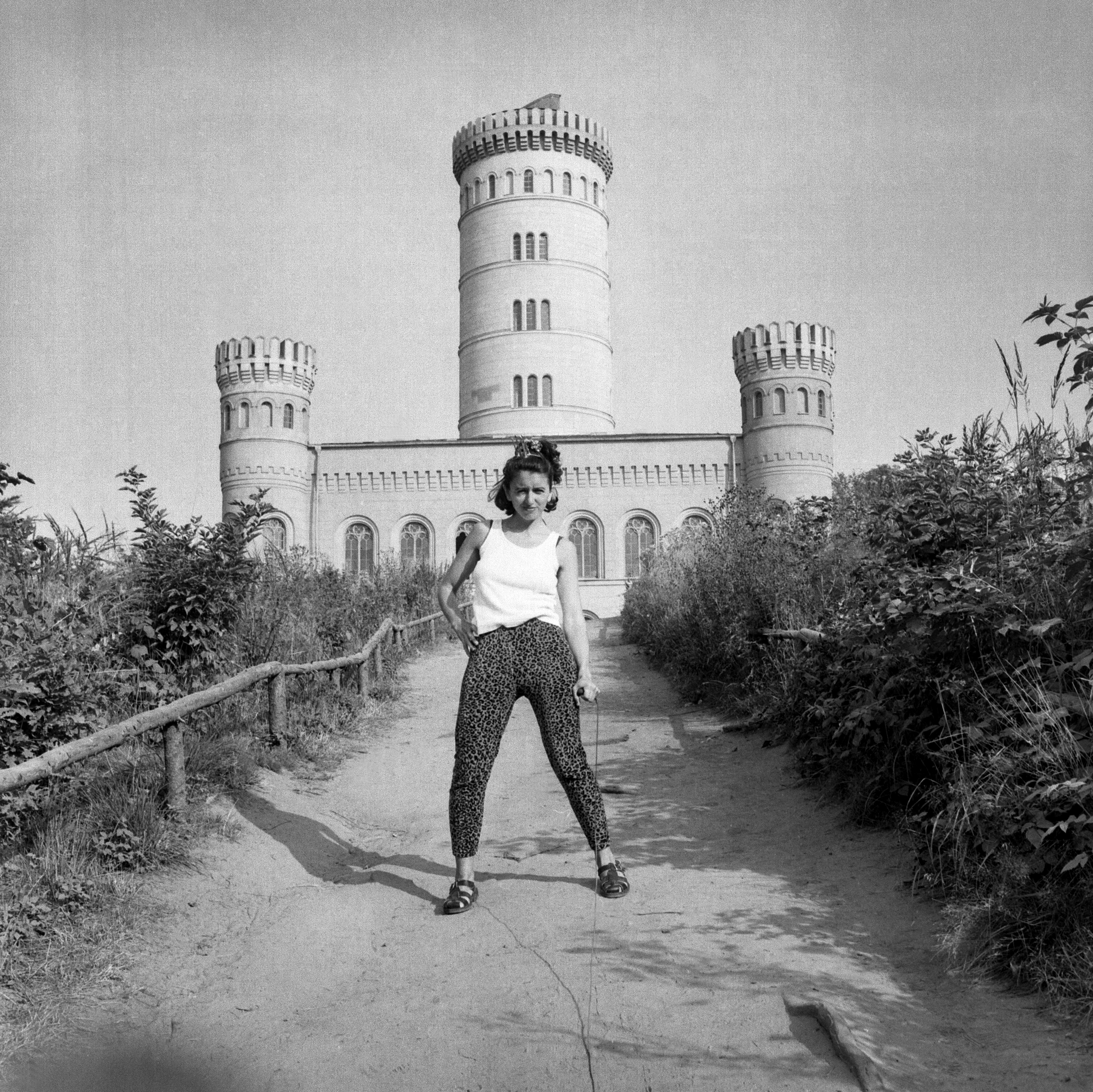

For me, self-portraiture, as a form of self-representation signifies both subject and object, vehicle, and space. I am interested in how experiences around identity, exile and migration are intertwined through reflection, memory and self-portrait as a tool. I start my working process in an environment where the surroundings become my image. The vantage point of my self-portraits is important, I often put myself in the center of the image, the reason is to be surrounded by the environment and to meet the gaze of viewer straightforward. I work intuitively - improvising the familiarity of everyday life twisted with some sort of distortion or perspective that is not in there. I don’t know exactly what I am looking for, so the process becomes like a moving image of examining gestures forward and backward to find itself truthful. In my late work I have finished the image editing digitally. As for props or costumes, I try to keep it close to where I am. (or who I am in the current moment) I wear my father’s costumes, my mother’s dresses, or my aunt’s nurse-costume, or I have found an item to pick up from where I stand. As long as it intuitively feels right I go for it. I try not to overthing the situation. I am interested in combining documentary photography with the concept of staged photography. Part of the process is also to find friction and tense between assimilation and resistance to the space and surroundings. I play with or against the idea of reality, identity, class, and ideology.

Geographically the locations are Sweden, former Yugoslavia, Serbia, Montenegro, Germany and England. But it could be anywhere, (except for the ones in the series taken in former Yugoslavia between 1991-93)

In my imaginary world they are universal. - Snežana Vučetić Bohm

::::::

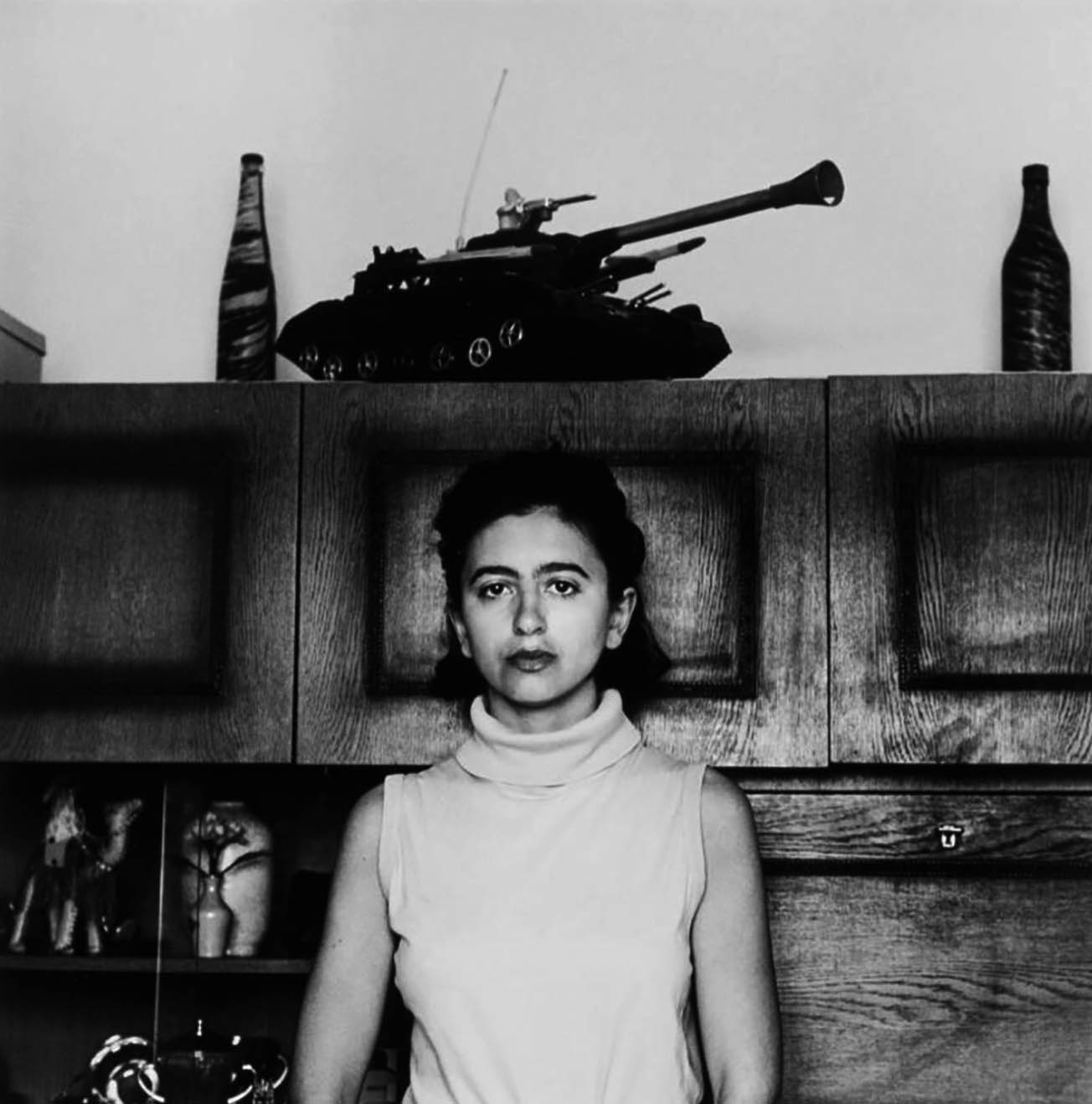

‘In 1991, when Snežana Vučetić Bohm was studying at Nordens Fotoskola, she was asked to make a documentary photo reportage. Equipped with a stand, a self timer and a Rolleiflex camera – a classic model for photo journalists – she travelled to Yugoslavia, which was on the brink of civil war. Her choice to work in black and white is also in keeping with a long tradition of photo journalism. But in the midst of the political conflict around her, she turned the camera on herself. Both the tank on the bookshelf in her cousins’ home and the barbed-wire fence in the landscape near her grandmother’s house seem to prophesy the looming war. Vučetić Bohm meets our gaze as both observer and observed, as the human being she is, in a terrifying and incomprehensible situation.’ - text from exhibition catalouge, Moderna Museet, 2022

::::::

Self-portraiture is a defining element in Vučetić Bohm's artistic journey, tracing its roots back to the very beginning when her father gave her the first camera. It has since remained an integral part of her practice, evolving alongside her experiences and perspectives.

Self-portrait is also a method that allows the artist not to be in the position of a witness, but to bring a human dimension and personal experiences into the frame. It becomes means for self-recognition, a process of confronting and embracing one's identity amidst the backdrop of global narratives and events.

The self-portraits in this exhibition are part of a larger series that the artist has been shooting for several years, returning to important places for the history of her family, and country of origin. We see the artist in her grandmother's clothes against the background of the family house or against the background of the monument to the victims of Yugoslavia in the concentration camp in Ravensbrück, or with the flag of a country that no longer exists. Looking closer, we notice the direct and questioning gaze of the artist and the tension from the hand holding the camera remote shutter as if a weapon aimed at oneself.

These non-reportage black-and-white photographs touch upon and reveal multiple facets and complexities of one single life: personal and collective, forbidden and beyond, traversing realms of gender roles, politics, and intergenerational trauma. And with their archival distance, they allow one to look at conflicts in a different way, highlighting the attempt to understand and go against the profound disconnect that often exists between individuals and nations where dialogue is stifled or nonexistent.

Can ever the state-sanctioned bloodshed be morally justified?

- Sona Stepanyan, curator, exhibition Victory over the Victory, Köttinspektionen, Uppsala, 2024

:::::::

Ethics and Infinity

Phillippe Nemo: According to war accounts, it is very difficult to kill someone who looks you in the eye.

Emmanuel Levinas: First of all, it is the straightness of the face, its straightforward, defenseless, way of showing itself, the skin of the face is the most naked skin, the most exposed. The most naked although its nudity is decent. And, at the same time, the most exposed. There is in the face an essential poverty, which is proved by trying to mask this poverty by pretending, by looking untroubled. The face is exposed and threatened, as if it invited acts of violence. At the same time, it is the face that forbids us to kill.

excerpt from, *Ethics and Infinity, 1981, a conversation with philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas and Phillippe Nemo

1991-1994

A study for Self Portraits, Gärdet, Sweden, 1991

A study for Self Portraits, Gärdet, Sweden, 1991